Introduction

Over the last few decades, there has been a clarion call from voters to make American cities navigable by bike. But despite billions of dollars in investment, no American city has made biking go mainstream, let alone made it a dominant form of transportation.

A bond initiative on the 2025 Denver ballot, presented to voters as a bonanza for bike and pedestrian infrastructure — though advocates agreed it was not.

The bike transportation high-water mark in Portland was in 2014. According to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey – a deeply flawed count – 7.2% of Portland residents commuted to work by bike.[2] Notably, this figure only represents people who commute to work, so it’s a subset of the population. It doesn’t mean they rode every day, and it certainly doesn’t mean that 7.2% of all trips were taken by bike. Since 2014, there’s been a precipitous and sustained decline in ridership. The 2024 edition reported more than a 40% decline since 2014.[3]

In correlation with growing investment, rates of bike transportation should be increasing. After all, riding a bike is affordable and convenient. More than half of trips in cities are less than three miles – an optimal distance for a bike ride.[4] You can cover this distance in about as much time as it takes to drive a car, you don’t have to hunt for parking, it’s inexpensive, and it’s healthy.

Unfortunately, the status quo approach to building bike infrastructure has failed to deliver meaningful results. There are two main reasons why:

We’ve built bike lanes but haven’t built complete bike networks.

The bike lanes we have built aren’t safe enough.

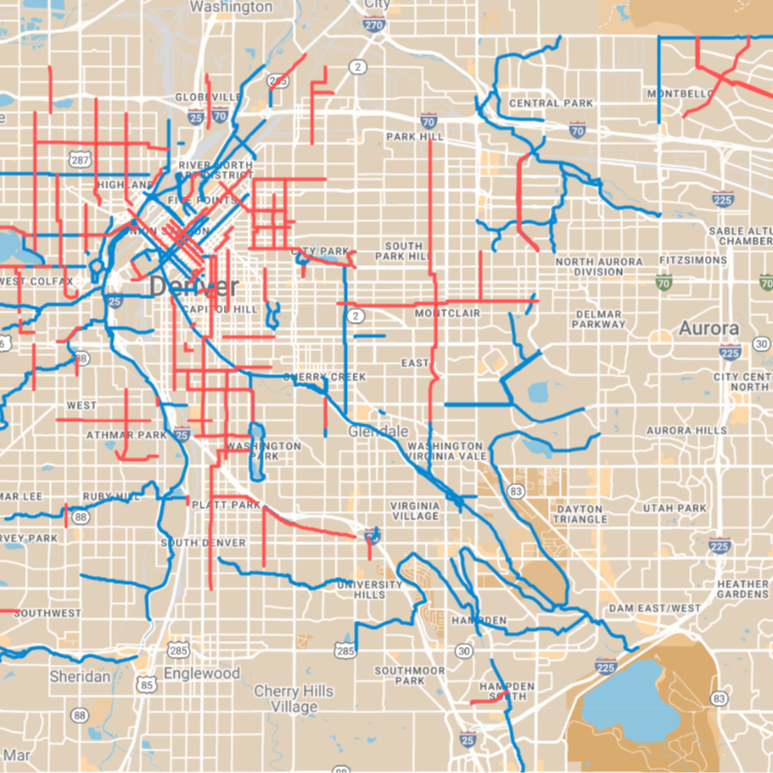

Decades into its development, the 2023 Denver bike map (in blue) didn’t constitute a complete high-comfort network. Nor would the completion of future bikeways (in orange) complete the network.

A bike network, in contrast to a bike lane, makes it possible to actually go places. It wouldn’t be possible to drive from New York City to New Jersey if there were no bridges or tunnels. You’d have a disconnected archipelago, some streets in Manhattan, some in Weehawken and Teaneck, but no way to connect them. That’s the basic state of bike infrastructure in America.

Cities have elaborate maps of future utopias in which connected networks make it possible to go anywhere by bike.[5] They also have eye-catching bike master plans with illustrations of happy families riding along tree-lined paths.[6] Someday, these documents promise, you’ll be able to do this.

Dallas refreshed its bike master plan in 2025. How we actually build it, is another question.

But the cold, hard reality is that while cities plan complete networks, they haven’t figured out how to build them. Instead, we settle for impossibly long development cycles and gigantic gaps in coverage. This lack of connectivity results in inadequate safety, low usage, and bikelash – angry responses from many of the very residents who voted for bike infrastructure in the first place.[7]

There are practical reasons why complete networks have seemed out of reach. Limited budgets and inadequate political capital have been especially significant barriers.

But the main problem is a retrograde approach to innovation.

Cities grind their way toward theoretical future networks in piecemeal fashion, one laborious bike lane at a time. Lanes end abruptly and aren’t connected to a network. Observation after we build something doesn’t happen. Iteration on underperforming designs is practically unheard of. And scalability isn’t on the radar.

Bike lane empty for a reason.

With a scarcity mindset, we lament and blame limited funding and political will.

We accept the idea that a bike master plan should take a quarter century to build. We accept that many seniors won’t have a complete bike network in their lifetimes. We accept that children will grow up without being able to ride bikes to the places they want to go. We accept that the costs of transportation will remain high, traffic congestion will continue to worsen, public health will continue to deteriorate, and climate change will continue irreversibly.

From a theoretical market standpoint, bike lanes are a product cities build for people to use. If cities were businesses, they would long since have gone bankrupt, because the product they release doesn’t generate adequate adoption.

“Product-market fit” is a self-explanatory business term, but a concept we haven’t adopted for bike infrastructure.[8] If customers don’t use it, you haven’t built a good product. If people are going to ride bikes, they want to feel safe for the entirety of their trip. And if they don’t feel safe, they won’t ride.[9]

Tellingly, if you ask most people to describe bike infrastructure in America, they’ll describe a type of facility that the vast majority of people will never use: the bike lane – a three-foot wide painted strip on a major street where drivers routinely exceed 35 mph, the threshold at which catastrophic injury in a crash becomes highly likely.[10]

An empty painted bike lane in Broomfield, Colorado. And an empty, wide, unused separated sidewalk calling out to be repurposed as a multi-use trail.

In Denver, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure doesn’t even consider conventional bike lanes to be “high-comfort” bike facilities – infrastructure that’s suitable for people of all ages and abilities.[11]

That we continue to build facilities that don’t meet people’s safety threshold and don’t connect – as if doing more of the same is going to fix the problem – demonstrates weak organizational learning. And organizational learning – observing what doesn’t work and iterating until you figure out what does work – defines modern innovation.[12]

We must cultivate an optimistic, abundance mindset that recognizes a wide array of great assets that already exist in the right-of-way, including interconnected residential streets, park trails, social paths, and sidewalks. And we can improve and connect these facilities into coherent networks now with low-cost tools like digital infrastructure, thermoplastic pavement markings, and preformed concrete.

Self-critique is hard. But the humility to acknowledge and analyze our shortcomings is also the wellspring of improvement and the foundation of a more scientific approach.[13]

References:

[5]Denver Moves: Bikes, the 2025 refreshed version: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f4fafe1405b6443da158f4d9e257887a

[6]The 5280 Trail, a visionary, but elusive loop around downtown Denver https://www.denverperfect10.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/5280-Acoma-Design-Principles_pages-LQ.pdf

[8] Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses (New York: Crown Business, 2011), "When you see a startup that has found a fit with a large market, it's exhilarating. It is Ford's Model T flying out of the factory as fast as it could be made, Facebook sweeping college campuses practically overnight, or Lotus taking the business world by storm, selling $54 million worth of Lotus 1-2-3 in its first year of operation."

[9] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2776010/

[10] https://aaafoundation.org/impact-speed-pedestrians-risk-severe-injury-death/

[12] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166497223001293

[13] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9244574/ “Embracing intellectual humility in science via transparent and systematic reporting on limitations of scientific models and constraints on generality has the potential to improve the scientific enterprise.”