Bike Networks Now!

A Modern Innovation Approach to Make Bike Transportation a Reality in American Cities

Version 1.0

By Avi Stopper

Dedication

To my kids. My dream was that in your childhood, you’d be able to ride your bikes anywhere in your city so you could be independent. That didn’t happen, but if we get this right, maybe your kids will be able to.

To my wife. I know that biking is your eighth choice for how to get somewhere. Thank you for riding with and indulging me.

To committed advocates and civil servants. Without your passion, we wouldn’t have made it as far as we have. Let’s take the next step.

The Organizing Question

Why is bike transportation still not possible for most people in American cities, and how can we make it a reality?

Strength in numbers on a group bike ride in Denver.

Despite decades of voter support for candidates who’ve run on the promise of affordable, healthy active transportation and billions of dollars of investment, bike transportation is still not a practical reality in American cities.

On the 2025 Copenhagenize Index, the global ranking of bike-friendly cities, the top American city was Portland, which ranked a paltry number 35 globally. [1]

America Thirty-Fifth!

Why are we so low? Simple: our cities aren’t bike-friendly.

To solve this problem, we need a revised approach to developing bike infrastructure based on three foundational components:

A modern innovation model based on testing, observation, and iteration – a.k.a. the scientific method.

An obsessive focus on complete bike networks instead of individual bike facilities.

A focus on riders of all ages and abilities, not just those who are confident.

The good news is that we already have the tools we need to be successful. These include widely accepted philosophical foundations like the NACTO Urban Bikeways Design Guide, Tactical Urbanism, and Quick Build. The toolkit also includes repurposable precedents that exist everywhere on our streets, but in incoherent bits and pieces: temporary conditions (a.k.a. construction), intentional and de facto diverters, and sidewalks that serve as multi-use paths. Now we need to tie them together in a coherent, quick-to-market approach based on scientific empiricism.

Construction creates a temporary traffic diverter — a de facto demonstration project — at Race and Colfax in Denver, CO.

If you’re immersed in the work of building bike infrastructure, planning, and mode shift, you’ll probably find some of the ideas that follow to be jarring, but I ask you to sit with them and reflect candidly on what the bike transportation movement has done well and where it has struggled.

An empty bike lane — for a reason.

Reflect on the shortage of outcomes, the continued lack of access for the vast majority of people, and the endless conflict involved in creating bike facilities. And reflect on the rapid acceleration of social ills: the affordability crisis, deteriorating physical and mental health, poor air quality, and climate change.

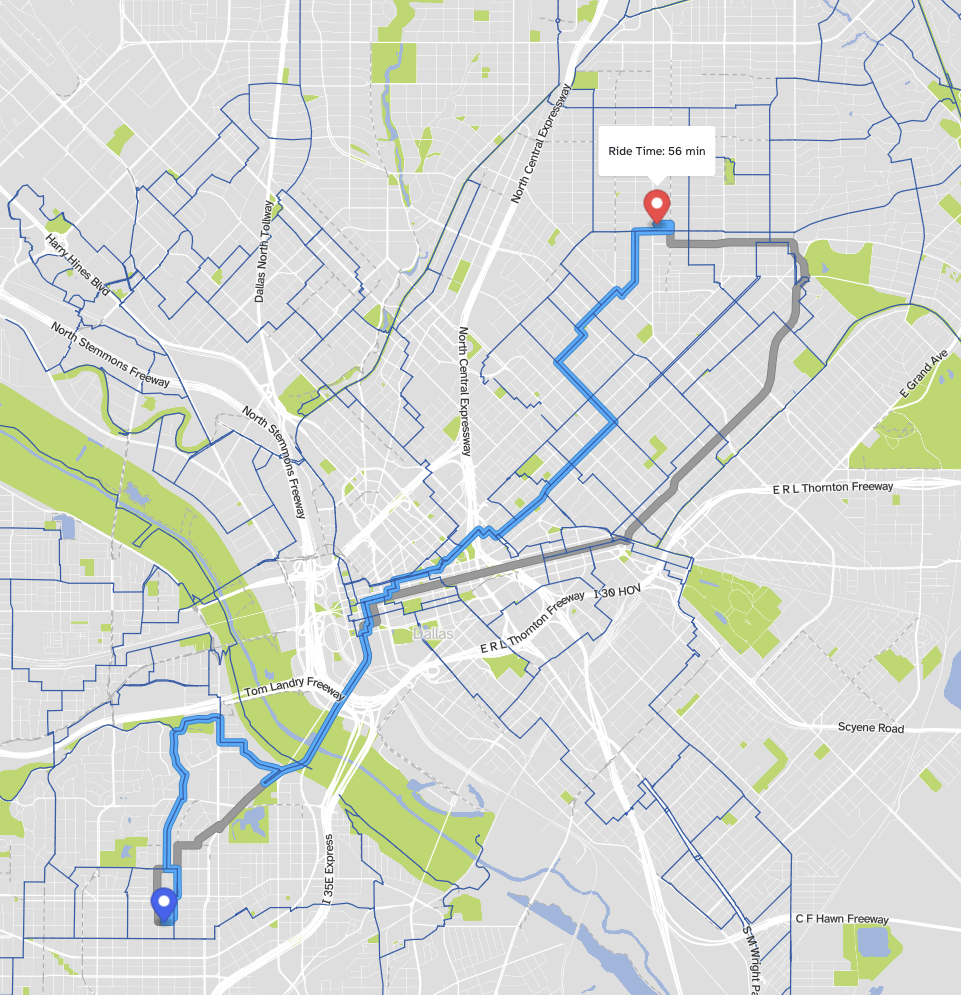

My team, Bike Streets, creates Low-Stress Bike Maps with advocacy groups and planners to make cities navigable by bike with the infrastructure that’s on the ground today. The maps aim to activate people today and build a groundswell of support for more investment in infrastructure.

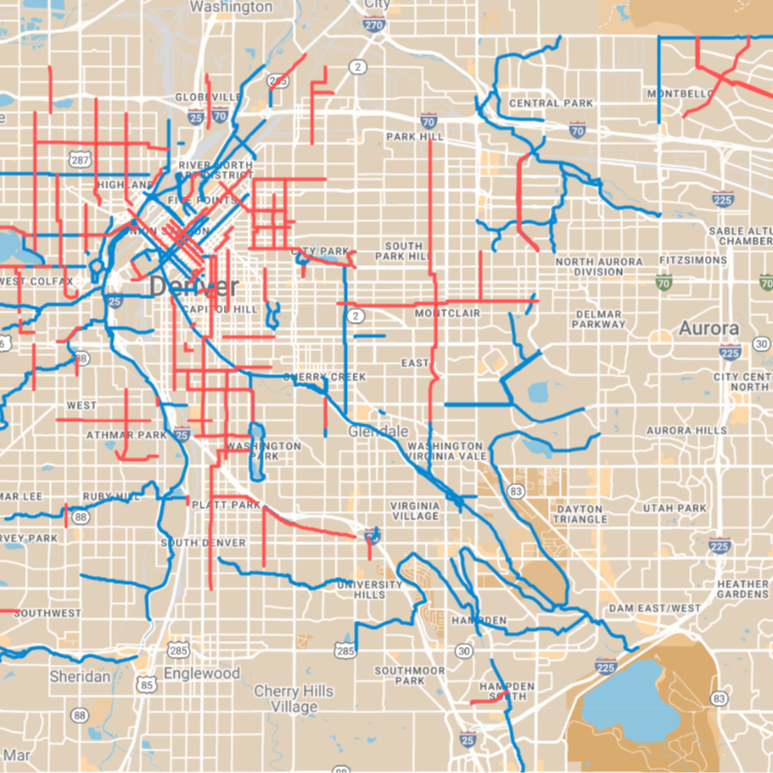

We always consider these maps to be works in progress. We first launched the Denver map in 2018. In 2025, we added the surrounding metro area and released dozens of new versions of the map. Low-Stress Bike Maps evolve as cities build new infrastructure and as our understanding grows of how to navigate a community by bike.

This book is also an evolving work in progress. I invite you to share constructive feedback and experiences to inform future versions, as we hone in on the optimal way to build complete bike networks now.

Avi Stopper, as@bikestreets.com

Introduction

Over the last few decades, there has been a clarion call from voters to make American cities navigable by bike. But despite billions of dollars in investment, no American city has made biking go mainstream, let alone made it a dominant form of transportation.

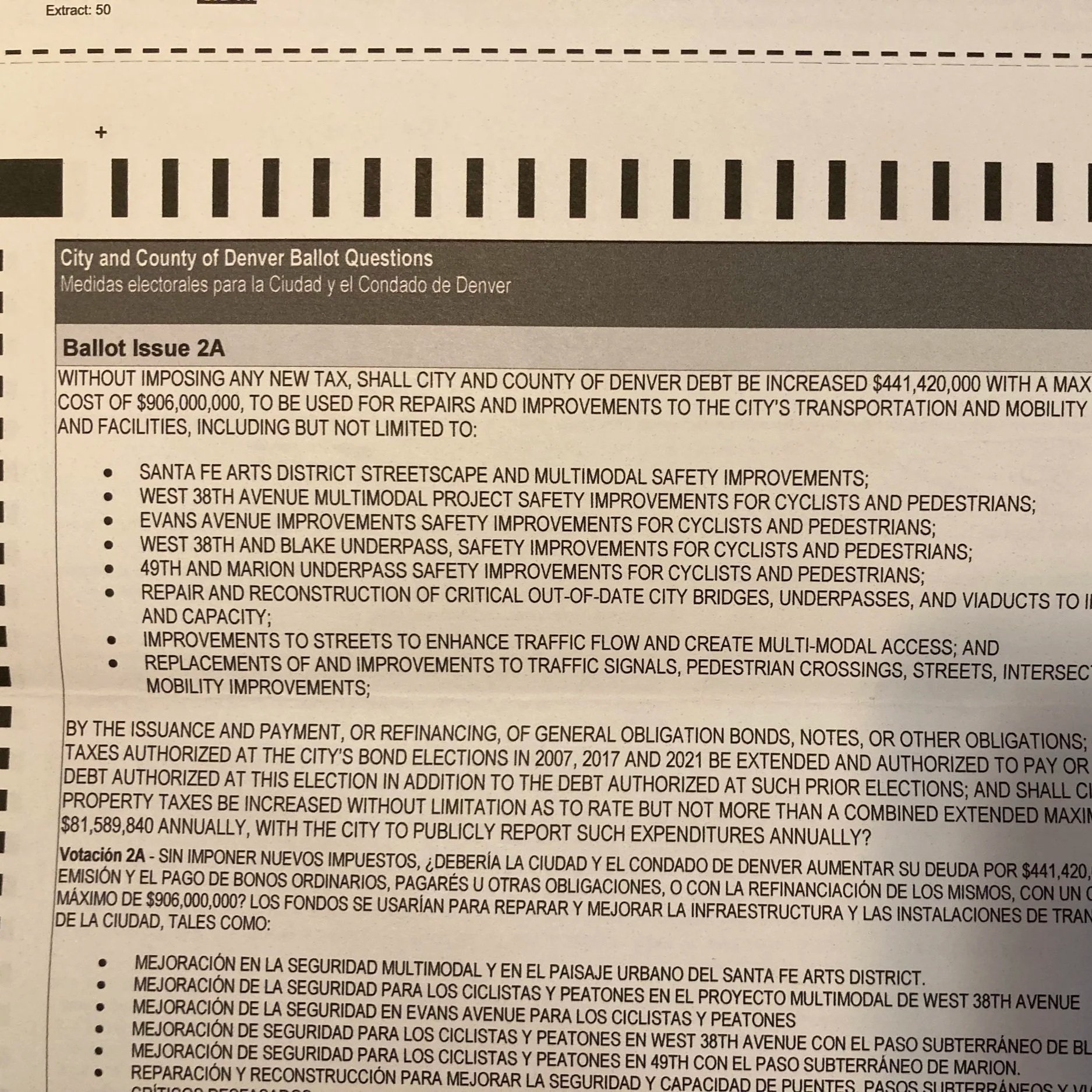

A bond initiative on the 2025 Denver ballot, presented to voters as a bonanza for bike and pedestrian infrastructure — though advocates agreed it was not.

The bike transportation high-water mark in Portland was in 2014. According to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey – a deeply flawed count – 7.2% of Portland residents commuted to work by bike.[2] Notably, this figure only represents people who commute to work, so it’s a subset of the population. It doesn’t mean they rode every day, and it certainly doesn’t mean that 7.2% of all trips were taken by bike. Since 2014, there’s been a precipitous and sustained decline in ridership. The 2024 edition reported more than a 40% decline since 2014.[3]

In correlation with growing investment, rates of bike transportation should be increasing. After all, riding a bike is affordable and convenient. More than half of trips in cities are less than three miles – an optimal distance for a bike ride.[4] You can cover this distance in about as much time as it takes to drive a car, you don’t have to hunt for parking, it’s inexpensive, and it’s healthy.

Unfortunately, the status quo approach to building bike infrastructure has failed to deliver meaningful results. There are two main reasons why:

We’ve built bike lanes but haven’t built complete bike networks.

The bike lanes we have built aren’t safe enough.

Decades into its development, the 2023 Denver bike map (in blue) didn’t constitute a complete high-comfort network. Nor would the completion of future bikeways (in orange) complete the network.

A bike network, in contrast to a bike lane, makes it possible to actually go places. It wouldn’t be possible to drive from New York City to New Jersey if there were no bridges or tunnels. You’d have a disconnected archipelago, some streets in Manhattan, some in Weehawken and Teaneck, but no way to connect them. That’s the basic state of bike infrastructure in America.

Cities have elaborate maps of future utopias in which connected networks make it possible to go anywhere by bike.[5] They also have eye-catching bike master plans with illustrations of happy families riding along tree-lined paths.[6] Someday, these documents promise, you’ll be able to do this.

Dallas refreshed its bike master plan in 2025. How we actually build it, is another question.

But the cold, hard reality is that while cities plan complete networks, they haven’t figured out how to build them. Instead, we settle for impossibly long development cycles and gigantic gaps in coverage. This lack of connectivity results in inadequate safety, low usage, and bikelash – angry responses from many of the very residents who voted for bike infrastructure in the first place.[7]

There are practical reasons why complete networks have seemed out of reach. Limited budgets and inadequate political capital have been especially significant barriers.

But the main problem is a retrograde approach to innovation.

Cities grind their way toward theoretical future networks in piecemeal fashion, one laborious bike lane at a time. Lanes end abruptly and aren’t connected to a network. Observation after we build something doesn’t happen. Iteration on underperforming designs is practically unheard of. And scalability isn’t on the radar.

Bike lane empty for a reason.

With a scarcity mindset, we lament and blame limited funding and political will.

We accept the idea that a bike master plan should take a quarter century to build. We accept that many seniors won’t have a complete bike network in their lifetimes. We accept that children will grow up without being able to ride bikes to the places they want to go. We accept that the costs of transportation will remain high, traffic congestion will continue to worsen, public health will continue to deteriorate, and climate change will continue irreversibly.

From a theoretical market standpoint, bike lanes are a product cities build for people to use. If cities were businesses, they would long since have gone bankrupt, because the product they release doesn’t generate adequate adoption.

“Product-market fit” is a self-explanatory business term, but a concept we haven’t adopted for bike infrastructure.[8] If customers don’t use it, you haven’t built a good product. If people are going to ride bikes, they want to feel safe for the entirety of their trip. And if they don’t feel safe, they won’t ride.[9]

Tellingly, if you ask most people to describe bike infrastructure in America, they’ll describe a type of facility that the vast majority of people will never use: the bike lane – a three-foot wide painted strip on a major street where drivers routinely exceed 35 mph, the threshold at which catastrophic injury in a crash becomes highly likely.[10]

An empty painted bike lane in Broomfield, Colorado. And an empty, wide, unused separated sidewalk calling out to be repurposed as a multi-use trail.

In Denver, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure doesn’t even consider conventional bike lanes to be “high-comfort” bike facilities – infrastructure that’s suitable for people of all ages and abilities.[11]

That we continue to build facilities that don’t meet people’s safety threshold and don’t connect – as if doing more of the same is going to fix the problem – demonstrates weak organizational learning. And organizational learning – observing what doesn’t work and iterating until you figure out what does work – defines modern innovation.[12]

We must cultivate an optimistic, abundance mindset that recognizes a wide array of great assets that already exist in the right-of-way, including interconnected residential streets, park trails, social paths, and sidewalks. And we can improve and connect these facilities into coherent networks now with low-cost tools like digital infrastructure, thermoplastic pavement markings, and preformed concrete.

Self-critique is hard. But the humility to acknowledge and analyze our shortcomings is also the wellspring of improvement and the foundation of a more scientific approach.[13]

References:

[5]Denver Moves: Bikes, the 2025 refreshed version: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f4fafe1405b6443da158f4d9e257887a

[6]The 5280 Trail, a visionary, but elusive loop around downtown Denver https://www.denverperfect10.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/5280-Acoma-Design-Principles_pages-LQ.pdf

[8] Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses (New York: Crown Business, 2011), "When you see a startup that has found a fit with a large market, it's exhilarating. It is Ford's Model T flying out of the factory as fast as it could be made, Facebook sweeping college campuses practically overnight, or Lotus taking the business world by storm, selling $54 million worth of Lotus 1-2-3 in its first year of operation."

[9] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2776010/

[10] https://aaafoundation.org/impact-speed-pedestrians-risk-severe-injury-death/

[12] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166497223001293

[13] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9244574/ “Embracing intellectual humility in science via transparent and systematic reporting on limitations of scientific models and constraints on generality has the potential to improve the scientific enterprise.”

Chapter 1. Science the Sh*t Out of This

In “The Martian,” Matt Damon’s character Mark Watney, stranded on Mars, looks at the camera and says soberly, “In the face of overwhelming odds, I’m left with only one option. I’m going to have to science the shit out of this.”[14]

Bike infrastructure is a means to an end: making bike transportation a practical reality for millions of people. This is a complex behavior change problem, and to have a shot at being successful, we need an innovation methodology that’s up to the task.

Empiricism and the scientific method embody the most powerful approach to innovation ever developed, but they’re collecting dust on the shelf. That needs to change.

With the status quo approach, we spend years on each project, employing a set of processes that have the patina of science – data collection, sophisticated simulations, and computer modeling – but are a far cry from the scientific method of hypothesize-test-observe-iterate. We’re overconfident in the results of our planning, as if what the models say will happen will indeed come to pass.

Planning should be about developing and testing hypotheses. It’s not a crystal ball.

With deep conviction, we invoke best practices and orthodoxy, recycling formulaic arguments like, “Average daily traffic on this street is 2,000 and average speeds are 30 mph. Therefore, if we put in a traffic circle, speed limit signs, and a speed bump, we will bring vehicle volumes down to 750 and speeds down to 25 mph. Therefore, many people will ride bikes here.” Maybe.

A kinda protected bike lane in Denver, as a driver monster trucks Ziclas.

A self-destructive assumption persists: conflict is inevitable and we just have to hold the line against NIMBYism. While there will always be naysayers, our approach to innovation must find common ground with more people so an unassailable plurality supports our projects.

Four years later, fatigued by countless hours of planning and design, we finally build the project. Rather than pulling up some (literal and figurative) lawn chairs to see if the outcome we predicted actually comes to pass, we move on to the next project.

Yours truly observes driver behavior at a critical intersection in Denver as part of a demonstration project we developed with the Colorado Department of Transportation.

From an innovation standpoint, this is a limited approach to building stuff that people actually use.

In a complex behavior change environment, the status quo approach misses the opportunity offered by the scientific method – the key to successful innovation is to test a hypothesis and iterate on it until we get it right. Moreover, we need to do this quickly. The protracted status quo approach takes on an excessive amount of risk in both time and money.

We persist with the status quo approach despite having an incredible array of tools from Tactical Urbanism to Quick Build. The use of these tools is the exception rather than the rule. And when we do use them, we often miss the most important steps. PeopleForBikes describes Quick Build projects as having four stages: demonstration (cones), pilot (flex posts), interim design (flex posts and planters), and permanent installation (concrete).[15]

Each successive stage should involve significant observation and iteration. Instead, we generally bypass the demonstration phase, jump straight to interim design, and then don’t make it a permanent installation. We get hammered by neighbors who detest the aesthetics of plastic posts and advocates who demand the final, hardened state. Most importantly, along the way, there was no iterative design based on qualitative and quantitative feedback. If the customers don’t like it and don’t use it, we need to go back to the drawing board.

A forest of plastic flex-posts at a Denver intersection — including one fallen soldier — promised as a temporary solution but never actually upgraded.

Any battle-tested innovator knows instinctively that no product is ever “complete,” that best practices are important starting points, and that constant learning through observation and iteration is the path to producing real results.

Mark Watney has deep foundational knowledge but learning how to sustain human life on Mars requires innovation through trial and error. In creating bike infrastructure, learning through trial and error and iterating is an afterthought.

To succeed in making biking a viable mode of transportation, we must embrace a modern innovation methodology that puts trial and error, iterative deployments, and empiricism at the center.

Shared Streets were an incredible pandemic program that was supposed to last two months. It lasted two years instead. 91% of people said they wanted them made permanent. And then they were gone.

A quote often attributed to Thomas Edison is, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”[16] It appears that what he actually said was this:

I recall that after we had conducted thousands of experiments on a certain project without solving the problem, one of my associates, after we had conducted the crowning experiment and it had proved a failure, expressed discouragement and disgust over our having failed ‘To find out anything.’ I cheerily assured him that we had learned something. For we had learned for a certainty that the thing couldn’t be done that way, and that we would have to try some other way.[17]

Edison himself.

That is applied science.

The path forward is actually a return to the basic scientific principles of the Enlightenment.

Chapter 2. Network First

Bike lanes have failed in America because they’re not safe enough and they don’t connect.

Narrow, frequently blocked bike lanes on high volume, high speed streets are a non-starter for most would-be riders.

How’s this for a network connection? A mere 30 stairs on the official Denver bike map.

The solution, at least in the abstract, is simple: build safe, complete bike networks. And not just at some theoretical point in the future. Now.

Ezra Klein, the New York Times columnist and author of Abundance says it best “We should be able to deliver dramatic changes to public infrastructure quickly.”[18] We have to reject the assumption that a complete bike network is a 30-year, multi-generational project. Every bike master plan must have a realistic plan of attack that answers the question: How are we going to build this in the next few years?

Cities have developed a compelling case for a “Housing First” approach to homelessness. Get folks some stability under a roof and they can start to rebuild their lives.[19]

Bike transportation needs a similar “Network First” approach where connected networks are the top priority – not just in plans and PDFs, but an on-the-ground reality in 1-3 years. That Version 1.0 will not be the fully optimized network, but it’s a start that can make bike transportation possible for many more people.

Four requirements guide a Network First approach:[20]

Complete version 1.0 network in less than 3 years.

Usable by people of all ages and abilities.

Massive actual usage.

Constant improvement over time.

A meaningful time constraint forces us to be creative. It also acknowledges a tricky political reality: we need to deliver while we have a supportive city council and mayor.

The additional requirements are designed to ensure access and outcomes: crappy painted bike lanes on arterial streets won’t suffice. We can’t just build it and walk away without studying the outcomes — or lack thereof — that we created. Infrastructure is a means to an end.

A de facto diverter and the picture we’re trying to create. Joyful streets filled with people going about their daily business.

The key place to start is with the recognition that every city has a high-comfort bike network hiding in plain sight. It’s probably not glamorous. There aren’t architecturally significant bridges or optimally engineered bike facilities like those that show up in the glossy PDFs cities create to show the vision of their future states.

But it’s a network that does the job for starters. It keeps people safe when they’re biking and makes it possible for them to get to the places they want to go. It’s the folk knowledge that locals have in their minds about how they navigate around town. It’s the set of routes that people on bikes are already using.

It’s the quiet residential streets, the hidden connector paths, and the park trails that people already ride.

We call this the “Best Available Network.”[21]

Best Available Networks, like the first one we mapped Denver and the subsequent ones we’ve mapped from Berkeley to Buffalo, show that it’s possible to create an initial network – today! – if we use every tool in the toolkit: trails, protected bike lanes, side streets, alleys, sidewalks, crosswalks, park trails, and so on.

Is it a perfect network? Not at first. But it’s vastly more accessible than painted bike lanes on arterial streets that end abruptly and spit you out in traffic. It’s a starting place. Over time we will prioritize and improve the weakest point locations to make it better and better.

The contrast between the status quo approach to creating bike infrastructure and a Network First approach could not be more stark.

| The Status Quo Approach | The Network First Approach |

|---|---|

| One bike lane at a time. Network maybe in the future. | Start with a complete network now. |

| Painted bike lanes on arterial streets are ok. | High-comfort facilities only. |

| Expensive, custom high-comfort facilities. | Low-cost, scalable high-comfort facilities. |

| Divisive public meetings. | Demonstration projects to build broad support. |

| Build it, then move on. | Build it, observe, and improve incrementally. |

| Huge expenditures of political capital. | Earn political capital. |

What’s critically different about the Network First approach is that we have a legitimate high-comfort network all along. A complete network isn’t just some theoretical future state; it’s today’s reality. People can ride today. We can build the bike movement now. And incremental improvements over time, make the network better and better.

This provides us with a glide path to all the expensive, custom features we imagine in the future. Rather than building Awesome Bridge A, Great Protected Bike Lane B, and New Trail C now and then figuring out how to connect them. We start with a complete network, get people riding, and then build A, B, and C.

We all love a good bridge, but what’s a bridge without a network?

Moreover, with a complete network, we have the means to build the bike movement (i.e., usage) now, which should accelerate our ability to get more and more investment in the network. We seek a virtuous circle: a complete version 1.0 network gets more people to ride, more people riding gets cities to invest more, more investment and the normalization of bike transportation gets even more people riding, and so on.

References:

[18] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/18/opinion/interesting-times-ross-douthat-ezra-klein.html

[19] https://endhomelessness.org/resources/toolkits-and-training-materials/housing-first/

[20] https://www.bikestreets.com/blog/4-requirements

[21] https://bikestreets.com/blog/the-best-available-network

Chapter 3. The “Urban Bikeway Design Guide” Revolution

The approach to innovation we propose on the following pages draws on three primary sources of inspiration. This book is a mashup of three texts from disparate fields that, in aggregate, can transform our hamfisted approach to innovation in the public right-of-way and make bike transportation a practical reality for millions of Americans.

The foundational tome is the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) “Urban Bikeway Design Guide,” which was first published in 2011.[22]

The book that launched a thousand bike lanes.

As you might expect from an organization with an 18-syllable name, the book is a wonkish tome of bike facility design. Curious how to design your “Bike Route Wayfinding”? NACTO’s got you covered (page 139.)[23]

That the book is decidedly not a page-turner belies its role as a harbinger of a revolution. For the first time, city transportation officials, as a collective, formally codified a vision for streets that went beyond moving as many cars as quickly as possible. This gave cities unprecedented cover to innovate on city streets.

In 2013, the Federal Highway Administration issued a memorandum supporting cities’ use of the Urban Bikeway Design Guide, cementing the book’s role in the way cities contemplate the use of the public right-of-way.[24]

The NACTO guide makes it clear that protected bike lanes and other “high-comfort” bike facilities belong on city streets and deserve space in the public right-of-way, and gives vivid design guidance for how bike facilities should be constructed.

The Marion Street protected bike lane in Denver.

This is a seismic shift from vehicular cycling and “sharrows” – a failed design paradigm and unfortunate portmanteau of “share” and “arrow” – that direct cyclists to share the same infrastructure with drivers, usually on high volume, high speed streets.

Sharrow hell near City Park in Denver.

The NACTO guide provides a methodology for building safe protected bike lanes, bike boulevards (quiet neighborhood streets made even quieter), and bike paths. With subsequent editions, the importance of connected networks has gotten more attention.[25]

A protected bike lane in Chicago.

But there’s still something conspicuously missing from the Urban Bikeway Design Guide: an innovation methodology for connecting these facilities coherently and quickly, grappling with how to create bike networks now given budgetary and political capital constraints.

An isolated diverter in Englewood, CO that isn’t connected to a network.

A well-designed protected bike lane, in isolation, can’t be successful unless your goal is for people to just ride back and forth. A systems thinking approach is essential: how does that bike facility connect to everything else – and not at some indeterminate point in the future? How does it connect people to the places they want to go now? If it doesn’t, because it’s not networked, it’s like a fiber optic cable that isn’t connected to the internet.

References:

[22] https://nacto.org/publication/urban-bikeway-design-guide/

[23] Second edition of the NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide.

Chapter 4. “The Lean Startup” and the Scientific Method

In 2011, Eric Ries published “The Lean Startup,” a thunderbolt in the startup community, that explores why so many innovation projects fail and how to increase the odds of success.

Note the subtitle: “How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses.”

Ries concludes, in essence, that innovation projects fail because they don’t use the scientific method.

The standard process of product development, the “Waterfall” methodology looks like this:

Do a huge amount of research. Ask people about their problems and what they want.

Spend a lot of time and money developing a product that we think will work.

Pull back the proverbial velvet blanket in a Big Reveal and release the product.

Watch as the results roll in and move on to the next project.

A seemingly spectacular bike facility near the National Western Complex in Denver — that doesn’t connect on either end to a network.

Sound familiar? This is the basic process by which we develop bike infrastructure. The problem is that we’re trying to change one of the most fundamental behaviors in American cities – how people get from one place to another – and we’re using a process that’s unscientific. Indeed, in the creation of bike infrastructure we forsake our intellectual forebears of the Enlightenment who developed, codified, and enshrined the scientific method as a means for discovery.

And “discovery” is truly what we’re trying to accomplish in the creation of new goods and services that solve problems people have.

This “Big Reveal” approach to innovation is fraught with risk: the risk of spending excessive time and money on innovation projects that don’t produce results. In developing bike infrastructure, risk is also encapsulated in the development of these projects that are then met with fierce opposition when it comes time to build them.

This flex-post forest in Denver caught most neighbors by surprise and caused a conflagration and intense bikelash.

Ries says, “The goal of a startup is to figure out the right thing to build–the thing customers want and will pay for–as quickly as possible. In other words, the Lean Startup, is a new way of looking at the development of innovative new products that emphasizes fast iteration and customer insight.”[26]

He proposes that we need to carefully manage risk through rapid, low-cost testing, and the creation of a “minimum viable product” based on a hypothesis that helps us understand if our proposed solution does indeed solve a problem.

Fast innovation in the right-of-way can be as simple as a few cones acting as a diverter and a series of observations to see how people interact with the temporary feature.

The influential entrepreneurs at 37signals take it one step further by proclaiming that “planning is guessing.” Sure, it’s informed guessing performed by people who are often experts, but it acknowledges that we don’t actually know how people will respond to a solution until we put it in front of them.

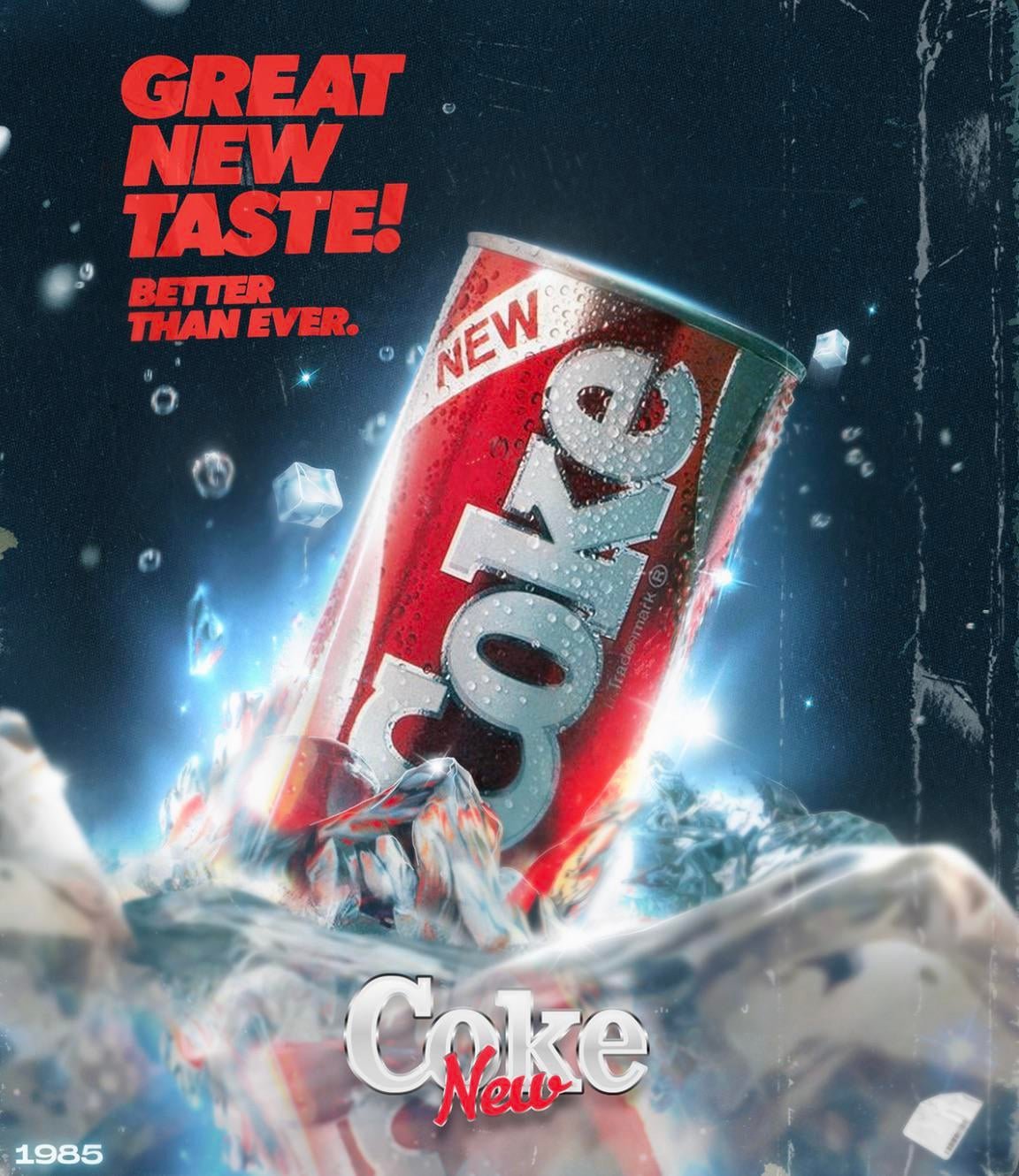

One of the most cautionary tales on this is that of New Coke in the 1980s. The company spent millions of dollars reformulating their flagship product. They ran an endless series of focus groups. In blind taste tests, the new recipe consistently outperformed the original formula. To great fanfare and with millions of dollars in marketing, they launched New Coke in 1985. The product flopped. No one bought it. 79 days later, the company killed New Coke and reverted to “Classic Coke,” bringing the original recipe back to market.[27]

It might have tasted better, but people didn’t buy it. And results are what matter.

Most of us who have done innovation in the private or public sector have had these kinds of experiences: incredibly protracted and therefore high-risk development cycles followed by product launches that land with a thud. It’s an exercise in serious humility and we learn the following the hard way:

Until a product is in the wild, we don’t know how it’s going to perform.

Accordingly, humbled innovators the world over have upgraded their processes to a method that derives at least some of its originating ideas from the Enlightenment, which is rediscovered through The Lean Startup:

Hypothesize: acknowledge that the product you’re proposing represents a belief that if we do X, Y will happen.

Determine how to test this hypothesis as quickly and inexpensively as possible. Time and money embody risk.

Run the test and measure carefully.

Interpret the results, identify what worked and what didn’t, and revise your hypothesis.

Test again.

Continue with this until you get the results you seek.

As Ries describes it, we need an approach that “Relies on 'validated learning,' rapid scientific experimentation.” He proposes a “build-measure-learn” cycle that starts with a minimum viable product and incrementally gets more sophisticated – based on empirical observation.

Orange barrels on Colfax Ave in Denver provided a validated learning of the traffic calming results of a lane diet.

Using minimum viable products and validated learning constitute a notably different approach to creating bike infrastructure. But we have to accept that getting people to ride bikes rather than drive cars is nothing short of a major innovation challenge. Coming at this from the perspective of experimentally based innovation gives us a fighting chance to create the future we seek.

The process of innovation shouldn’t just be applied to the development of products and services. The process of innovation should also be applied to the innovation process itself. We must constantly be observing our own work, our own process, and identify where it works and where it doesn’t. And where we observe opportunities for improvement in the process, we should implement them and observe dispassionately whether we did indeed improve.

References:

[26] Ries, Eric. The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. New York: Crown Business, 2011.

[27] https://www.qualtrics.com/articles/strategy-research/coca-cola-market-research/

Chapter 5. Exhibit A for “Abundance”

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book “Abundance” calls out the inability of blue cities and states over recent decades to build the stuff that voters want: housing, high-speed rail, and the medical breakthroughs we desperately need.

“Countless dollars,” they observe, “Were spent on health insurance, housing vouchers, and infrastructure without an equally energetic focus on what all that money was buying and building…It revealed a disinterest in the workings of government. Regulations were assumed to be wise. Policies were assumed to be effective. Cries that government was stifling production or innovation typically fell on deaf ears.”[28]

Bike transportation exemplifies what they’re talking about: an enthusiastic and supportive public, lots of money spent, and very little in the way of meaningful results.

A seemingly well-designed feature connected two offset segments of a bike boulevard in Denver. But where are the riders?

Making bike transportation possible in cities is something that pluralities of voters have demanded for decades. According to a 2025 YouGov survey, “Americans are much more likely to support bike lanes in their local area than to oppose them (76% vs. 15%).”[29]

In 2024, voters across the country approved $24.7 billion in spending on bike infrastructure.[30]

People want bike transportation to be a reality in their communities and they’re ready to invest their tax dollars in it.

This stated desire of voters, however, crashes up against the rocks of implementation. The objective reality is that cities have failed to make bike transportation something that people of all ages and abilities do to get around.

An empty bike lane is not a win. Building something isn’t good enough. It’s getting people to use it that matters.

In no American city has biking become a primary mode of transportation for a large swath of the population. Portland, Oregon, which is widely considered to be the best bike city in America, does a remarkable annual Bike Count with more than 170 volunteers stationed across the city. Since 2014, there’s been a sustained decline in ridership. The 2024 edition reported more than a 40% decline in biking since 2014.

During the 2014 high water mark, according to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS), 7.2% of the Portland population who commute to work rode a bike.

As John Simmerman, founder of Active Towns says, “I consider the ACS data to be so inaccurate that it serves as a distraction, and it doesn't come anywhere close enough to estimating how many people ride.” We don’t even have decent data.

Nonetheless, it’s the data we have. And the nationwide picture is bleak. In a country of 340 million people, less than a million biked to work in 2024. The percentage of workers who primarily bike to work has flatlined since 1980 at .5%. And a paltry 1% of total trips are taken by bike.[31]

We as bike advocates, planners, and transportation officials shouldn’t paper over this with vanity metrics like the number of dollars we’ve spent on infrastructure projects or the miles of bike lanes we’ve created.

This is not what results look like.

This is what results look like. We cannot rest until we’ve created this picture everywhere.

Instead, we need to acknowledge that we’ve fallen short in actually getting people on bikes and we need to revise our approach to create the future we seek: not just one in which people can theoretically ride bikes to the places they want to go, but a future in which they actually do it.

We keep doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. We keep hitting the same pitfalls: excessive conflict, ballooning budgets for individual projects that are illogical in the context of complete and connected bike networks, an excessive dependence on consultants, protracted development timelines, and the most problematic of all: a lack of outcomes even vaguely approaching a transportation transformation.

“Abundance” is a powerful guide, because it opens a conversation about why we don’t have the cities we want. And the place to start to produce the results we seek is by being honest with ourselves about where we currently are.

References:

[28] Klein, Ezra, and Derek Thompson. Abundance. New York: Avid Reader Press, 2025.

[29] https://today.yougov.com/travel/articles/52404-three-quarters-of-americans-support-bike-lanes

[30] https://www.peopleforbikes.org/news/voters-approve-27.4-billion-for-better-biking-2024

[31] https://data.bikeleague.org/data/national-rates-of-biking-and-walking/

Chapter 6. Time and Money Equal Risk

One of the most surprising qualities in exceptional innovators is an ability to carefully manage risk, which comes in the form of time and money.

Low-cost, temporary, built-in-a-few-weeks Slow Streets in San Francisco embodies a low-risk approach to innovation in the right-of-way. But alas, this isn’t the norm.

This preoccupation with risk management is counterintuitive. In popular perception, entrepreneurship and innovation is about making big bets. That’s certainly one approach: OpenAI expects to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on data centers and hardware in the next five years and doesn’t expect to be profitable before 2030. [32]

In scenarios, however, where we’re constrained by reality and our time and money aren’t infinite, we need to carefully manage those precious resources.

Risk, in the creation of bike infrastructure, looks like this:

We hire an expensive but renowned consulting firm to design a bike lane. Over two years, we hold multiple community meetings. 10, 25, maybe 50 people show up to these meetings even though there are 10,000 people who live within a mile of the facility we’re planning.

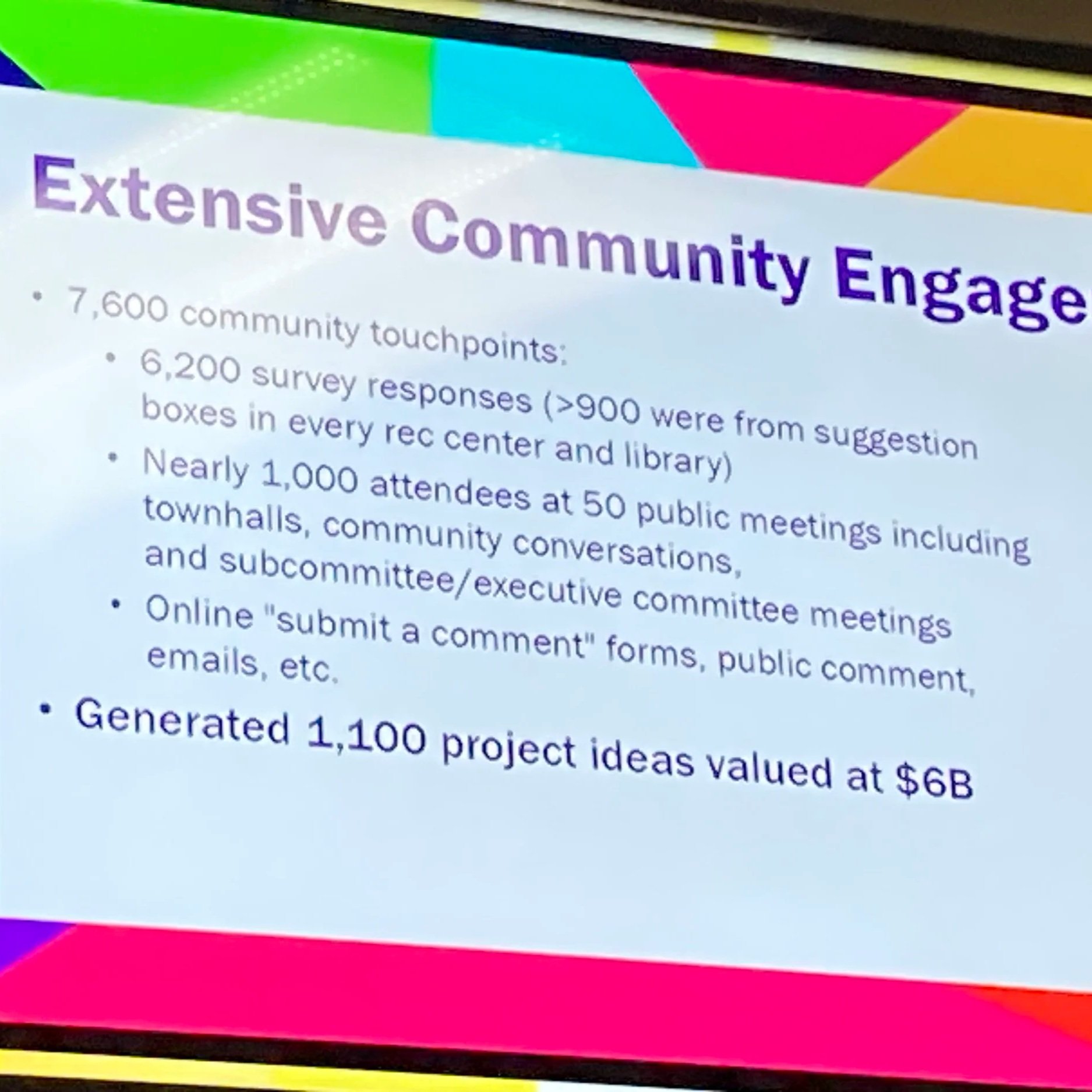

A slide from the 2025 Vibrant Denver Bond pitch deck trumpets 7,600 community touchpoints — that’s barely 1% of the city’s population — and 50 public meetings across the city with an average of 20 people per meeting.

We show people drawings of what it might look like and ask them to imagine their future selves in those locations. What will they like about this and what won’t they like? It’s as if we designed the process for failure around Projection Bias, “A self-forecasting error where we overestimate how much our future selves will share the same beliefs, values and behaviors as our current selves.” [33]

If you’ve been to a public meeting, you’ve seen drawings like this one from the 5280 Trail, an amazing potential project in Denver that has been in the works for a decade. Now imagine how you will use this in another decade when it’s built.

A small group of supporters are vociferously in favor of it. A few opponents are strongly against it. The consulting firm, sensitive to everyone’s voices, and intent on being inclusive, makes compromises in the design. No one is happy. The pro-bike crowd yells at the city for prioritizing driving over safety. The anti-bike crowd shouts about how disastrous this is going to be for local businesses and how much it will increase cut-through traffic on neighborhood streets.

A provocative blog post from Strong Towns, “Who is the ‘Public’ at Public Meetings?”, summarizes this dynamic:

Public input is valuable. However, conventional mechanisms of public input may provide a distorted picture of what those with a real stake in a place actually believe or want. Whole classes of people might be marginalized from the process, while elected officials end up catering to a perceived "public" that is actually much narrower and more homogenous in its views and interests. [34]

This process – for a single bike facility, nevermind a complete network– takes years. A new mayor who lacks the vision of a bike-enabled future is elected, and there’s a downturn in the local economy. Funding for bike infrastructure is slashed, so we make further compromises in the design. We’re going to use plastic flex-posts rather than concrete. Another year passes.

At last, it’s time for construction. A forest of plastic flex-posts springs up in the neighborhood, enraging and activating folks who didn’t tune in to the original process. They make a website and circulate a petition. They email their city councilperson, who was barely reelected and depended on contributions from some of those same people.

A flex-post forest on 7th and Williams in Denver that created a maelstrom.

The city councilperson puts in a call to the department of transportation and mayor, who then announce they’re going to review the design. The review unfolds much as you might expect. Those with political power – neighbors and business owners prevail – and the resulting design is diluted to the point of uselessness for all but the most confident cyclists. Headlines appear in local news outlets like, “Denver makes changes to 7th Avenue intersection amid criticism from neighbors, cyclists.” [35]

The outcome, predictably, is poor and self-fulfilling. Few people use it. People driving by see the empty bike lane and sour on bike infrastructure. Everyone is exhausted and demoralized, but we get up, brush ourselves off, and do it again. Back to the salt mines we go.

Some permutation of this process is what we see over and over and over.

In terms of time and money, it’s an incredibly risky path to creating bike infrastructure that actually gets people riding. And in the context of building complete bike networks for all, it’s a failed paradigm. It’s tragicomically ineffective, but it’s the process that unfolds on streets across the country. This is how we end up with 25-year projected timelines for the completion of bike networks. This is how we end up with underperforming individual bike lanes to nowhere. And this is how former supporters become opponents of bike infrastructure.

An acknowledgement of these risks, a willingness to be self-reflective on what works and what doesn’t, begins to offer us an offramp from this sisyphean approach.